Bridge Busters

The World Renown Dambusters got their name in the Korean War for various feats. I was privileged to be a member when the squadron first deployed with the A7E to Vietnam. I was on my second cruise when we deployed in 1972 and, among other collateral duties, was the squadron landing signal officer.

When we went back over North Vietnam, interrupting logistics was one of our objectives. As things started heating up, bridges were on the forefront since most of the country during the rainy season is under water and bridges connect the various roads and dykes between the flooded fields. We were not yet going above the 19th parallel at that point. We also hunted down trucking, cut roads and railroads, went after military installations, SAM sites, AAA sites, radar sites and anything else that could put us in harm’s way. Much of our strategic targeting was nonsense coming from the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Our 110 baud teletype messages were not the best means of conveying all the data generated by a war in progress so their intelligence was almost always stale. I can remember going back against targets three times that we had destroyed on the first raid, where the only thing left were the guns which we faced while trying to find something worth blowing up.

Since it was difficult to hit a small bridge structure, even with our superior bombing skills and our sophisticated bombing system, which was the best in technology for that day and time, someone up the chain decided we needed better weapons for the job. Out came a new weapon, the Walleye, a television guided glide weapon. There was a smaller version around a thousand pounds if memory serves, and the one we called “Fat Albert” that was 2260 pounds. For the small bridges we saw on a daily basis in country the small Walleye was an appropriate level of destruction. The way the Walleye worked is it gave us a picture on our radar scope (black and white) of what the camera in the weapon was seeing. We had it bore sited initially and would aim with the manual bomb site until we saw something we recognized on the scope and then would maneuver the aircraft until we saw the specific and hopefully high contrast picture we thought would guide the weapon to create the best effect. We would then designate the target and the tracking head of the weapon would be released and it would (hopefully) stay locked on the picture we gave it. Such things as windows on buildings, or other items that had boundaries seemed to work the best.

We learned after delivering a few of these things that they had a bias in a specific direction, down and left if I recall, and if a contrast line looked linear in that direction, it might track down that line. Specifically we saw if you locked up a ship, it might track down the scupper line on the deck and end up being aimed at the pointy bow of the ship. And as such, it would do little if any damage hitting the ship at that point. This added some serious complexity to the attack, since now one had to analyze the object for best geometry to get good tracking. Sometimes that best geometry put one further into harm’s way or at least kept us in the gun sights longer than we might want.

Nevertheless, they were a boon for the bridge busting business and the molten metal warhead did a great job of cutting in two anything that came in its path. A couple of times a week we would man up with two Walleyes per bird and do armed reconnaissance up and down Route One, and the various north/south roads on the back side of North Vietnam. North Vietnam was a bit like a mirror image of California, from whence we came, except smaller. The coast, a range of mountains, a valley, more mountains, then Thailand. Very similar topography on a small scale.

One such area was Vinh Son. While it had a major logistics route, it also had major protection. Our moniker for doing armed recce in that area was providing targets for the Vinh Son gunnery school. Both sides of the road seemed to be lined with AAA, mostly 23mm and 37mm. While these smaller guns did not have the altitude reach of the larger stuff, they were more flexible in rapid aim and had more rounds per minute capability. You could tell which weapon was shooting at you by the number of tracers, since each gun had a different clip size. These were basically World War II mounts that were being pressed into service, but effective at disrupting a bombing run for sure.

As we got better with the small Walleyes and commonly came back with a bridge per Walleye to our credit, we heard that there might be a new version coming out. Since the Vietnamese seemed to be able to rebuild a bridge almost over night we had no shortage of targets. Plus there were some much larger bridge targets that seemed ripe for the weaponry but we had not been fragged for those.

The Smaller Walleye

At some point, our skipper briefed us that we had been chosen, because of our bridge busting capabilities, to sponsor an effort from China Lake to try out a new weapon they had developed. It was top secret and it was not something we could talk about even aboard ship except in the briefings to follow. I heard they were bringing 25 engineers on board to help with this program. I wondered out loud where they would put that many VIPs since a large number of our junior officers were relegated to JO bunkrooms instead of staterooms. We never did find out where they slept, but we got to know a few of them personally as we were briefed on how this weapon would be deployed.

As the landing signal officer, I had very good carrier landing grades and was typically in the top ten in the airwing among over a hundred pilots in various types of aircraft. Our avionics officer was a NESEP. That is, he was a former enlisted electronics technician that got sent to college by the Navy, got a degree and a commission, then sent to pilot school to learn to fly. His kids were old enough to babysit our kids. He was also very sharp in electronics. I was no slouch myself, with strong formal EE training in college. I also went to Electronics Warfare school to learn how that stuff worked so I could teach pilots appropriate tactics and technical acumen to effectively combat Soviet radars, etc. The two of us were chosen to be the first ones to carry this new weapon.

We sat down with a small crew of engineers that showed us the system. One aircraft would have the control box under his wing which contained the data link to talk to the weapon and also record the video. The other aircraft would carry the weapon, aim it and release it. The obvious advantage here was that the glide weapon had a good range, it could be released miles from the target, and the releasing pilot could leave the area. The guiding aircraft would be completely out of harms way so he could just concentrate on guiding the weapon precisely toward the target. Supposedly the data link had a range of 40-60 miles although we never tested it out that far. The releasing aircraft would have video on the scope just like the other Walleyes, whereas the guiding aircraft would not only have the video from the weapon prior to launch he would also have live video and the ability to move the aim of the weapon all the way to impact.

The engineers brought five hand built weapons with them. Because of the expense of each weapon (we were told millions at the time) and because if there were failures they would want to find out what went wrong, we were instructed that if we did not release a weapon that it would be brought back. That was a bit problematic since these were the Fat Albert sized models. We carried them on the inboard station and to balance out the wings we also carried a thousand pound Mark 83 general purpose bomb on an outboard station on the opposite wing. The combination of these two weapons, which we needed to balance the loads for both the catapult shot and the landing, left us with only 500 pounds of gas if we needed to bring one back. Each weapon was to be delivered against a specific target. There was no practice.

Since I had the best landing grades, I was designated to carry the bomb. We had carried a Fat Albert or two but had always shed those loads on something before coming back to land. I recall taking out two railroad engines and a bunch of track with one weapon. No one had landed with one. I was assured by the engineers that the moments of the two bombs should cancel out nicely. Of course, no one was talking about the fact that I would most likely only get one shot at landing it since I would probably run out of gas if I had to go around. The A7E burned about 3500 pounds an hour just running level, so the 500 pounds gave me about 8 minutes of flight time before flame out if I had to go around. Needless to say, I did not dwell on those figures.

The preflight was nothing special, just a big white whale suspended under the wing and a typical green bomb with a yellow stripe and mechanical fuse on the other wing. Less drag than our typical ejector racks (MERS and TERS) full of 500 pounders. Not much different at all than the normal Fat Albert’s we had carried a few times.

The control box hung under the parent rack, was smaller than any bomb we carried, so did not seem to have any ill effects in terms of airplane handling, etc. Plus it only weighed about a hundred pounds so did not affect the landing weight significantly. So far so good.

The briefing had been interesting. Our first target was to be a coastal defense site near the north side of a large bay that was about 6 miles across. It was a 105mm gun on tracks that was hidden in a cave in what looked like an Oregon cinder cone from a volcano. Just a big, pointed, smooth looking mountain that was probably hundreds of feet high if not a thousand. The 105mm would be run out, lob some shells at our destroyers off the coast, and then run back inside the mountain. We all assumed this was a small tunnel large enough for the gun and a couple of gomers to run it, and a small cache of ammo. Geno and I looked at the pictures to get situational awareness of the area around it. They had warned us that since the system did not have a zoom lens, we would have to find the mountain in the video, release the weapon, drive down to the white caps on the shore line, find the perimeter road just above the shore leading to the mouth of the cave, then move laterally until we could zero in on the opening. I had done a medium angle loft bombing run on the same target under some typhoon weather once before so was familiar with it down at sea level. I was pretty sure we could see the opening from about ten miles out if we were pointed at that side of the mountain.

We did the standard briefing, with the emergency of the day being low fuel. The intel briefing showed we were skirting a SAM site but should probably be out of range of a launch. We would be delivering over the bay so no AAA would be a threat. I decided to carry the TOPCON 100 SLR with me. It was a bit problematic since there was no place in the cockpit to secure it. It just sat on the right hand side electronics panel on top of the transponder controls. We briefed the altitude and distance we would need in order to have the appropriate glide angle so Geno would have ample energy to maneuver the Walleye. I would put the camera on something recognizable and get a confirmation from Geno that he had the image, then designate the weapon to lock the gimbals on the area and launch it. He would drive it in and find the mouth of the cave. I would stand off a few miles and see if I could see anything on the ground when it hit. We were told since it was not really a blast weapon that probably all I would see is a little smoke, which is what we usually saw with the small Walleyes.

We were cautioned not to use words that would give away what we were doing or the nature of the weapon we had on board. We shook our heads a bit when this came up. The Communications Security group had been on board and they were a serious joke. Since they seemed to know absolutely nothing about carrier operations their recommendations and comments about our communications made for better cartoons on the back of the air plan. We had been instructed if we heard someone violate the security of communications we were to broadcast “Beadwindow” and a code indicating the type of violation. The Airwing Commander got a Beadwindow and the cartoon on the back of the airplane showed CAG launching off the catapult and broadcasting “Viceroy 502 airborne.”

“Beadwindow – divulging aircraft capability!”

We could only surmise what fun this flight communication was going to be, but we made up a few code words to keep ourselves off their list. Our personal brief basically said the mission and our safety is more important than comm security and if we needed to talk we would.

The launch was uneventful. We joined up and headed out for the coast line. Geno stopped about 10 miles off the coast and set up a race track orbit. We wanted the antenna of the control box to be pointed toward the target for best signal at the time of launch so some communication was necessary to get set up. I continued into the middle of the bay and set up a race track pattern in the direction of the mountain. I could make out the white of the shore line but not very definitively. But the mountain was obvious so I assumed we could pull this off. We coordinated our race tracks such that when I was approaching launch distance, Geno was just heading inbound. Since he was a long way away he could drive steady state in a straight line without being an easy target, something we all saw the value in.

I approached the launch distance, put the pipper on the shore line and could see the white of the surf. I checked with Geno and he could see it as well. I designated on the shore line and punched the bomb release. I was concentrating so much that the release caught me by surprise. When you drop two thousand pounds off one side of the airplane it wants to go the other way quite rapidly, and I was in a 90 degree angle of bank to the right when I put my head up again. I recovered the airplane and circled around to head back in to watch what happened.

Geno saw the shore line and drove in for a while. As things got clearer he could make out the road and brought the aim point up to the road and started moving laterally along the road. He quickly got to where he could see the mouth of the cave. We had both wondered out loud what effect the engineers expected putting a molten metal warhead against the mouth of a cave, and they assured us that it might close out the cave, and it could cut the railroad tracks so that they could not roll out the gun. Mostly, they wanted to see the first data link Walleye tracked to a real target.

As the mouth of the cave got clearer and started to have some definition, literally a few seconds before impact, Geno saw that the cave went to the left. With appropriate timing he jammed the stick to the left as the Fat Albert reached the mouth of the cave. At this point I had just completed a turn and was pointed back in. A fiercely bright orange flame shot out of the cave a distance that was about the radius of the mountain itself, I estimated at least a half a mile. It was shocking and not at all what I expected. I picked up the camera, turned it on and since it was already set up for infinity focus I just raised it up and shot a few pictures, but the flame had already fallen back to probably two hundred feet or so. I drove in and looked at the mountain. There were still some flames coming out of the cave and lots of smoke. Mission accomplished. We headed “bock sheep.”

As we were debriefing the intel folks and the engineers, word came in from an A6 in the area that the whole top of the mountain had caved in and the overall height had dropped a couple of hundred feet. Apparently the small cave was not small at all, but a large storage and ammo facility of some sort that was occupying the whole inner mountain. When I went back there a few days later it was truly unbelievable that the whole mountain looked to be hollow and caved in. But fun!

I had handed my film to the Photo Interp folks on the way in. As we were describing what happened the engineers, seeing an opportunity for great PR with the funding folks back home, asked if I had gotten a picture of the flame. I had to say, unfortunately, no. They were very disappointed. Later that day, the intelligence officer called me up to IOIC.

“The photo guys have something to show you.”

“Okay, what do you have?”

“You said there was a flame a half mile out there, right?”

“Yep. That is what I would have called it.”

“Of course the flame is not there, but look out here on the right side of the picture. That is two miles out in the bay. There is a bunch of stuff hitting the water out there so I would say your estimate is probably right on or a little conservative.”

“Nice work, guys! I appreciate it.” Stuff hitting the water two miles away. Obvious a secondary from what ever we hit in the cave, which would have to be a fairly large cache of high explosive of some sort. Nice, nice, nice.

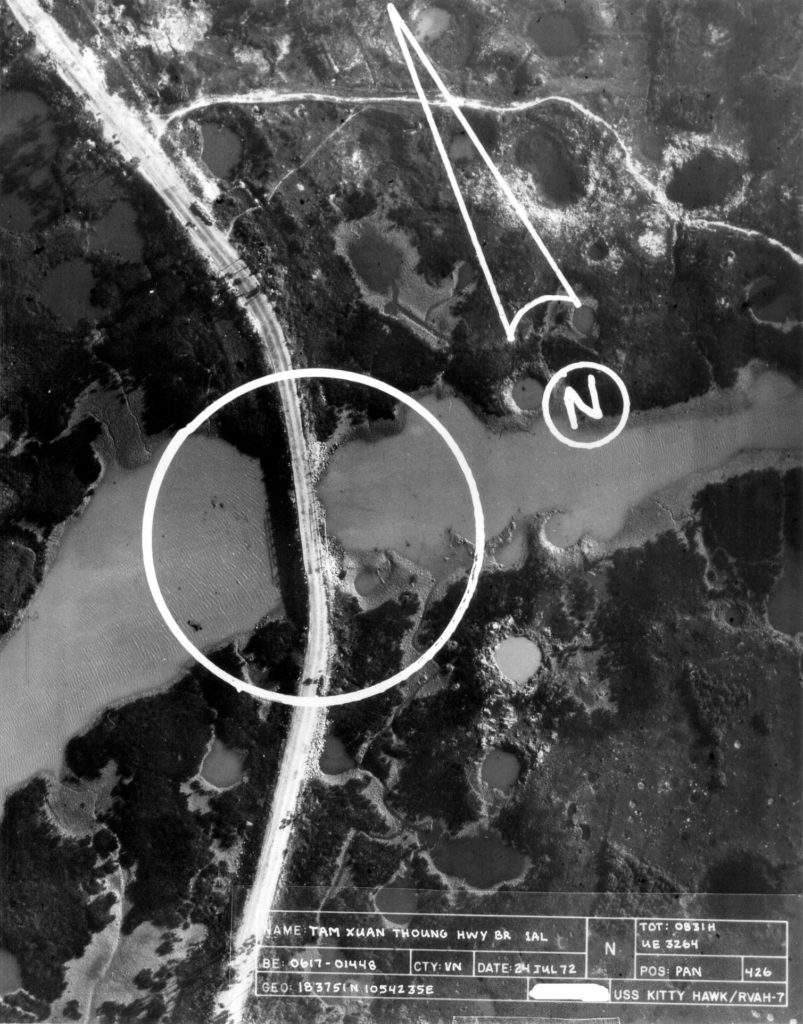

Now the guys were excited to get the next one airborne. The engineers were obviously ahead of the game. We were invited into a briefing with some new faces. Apparently these guys were civil engineers. They put up a picture of the Ninh Binh bridge. We had put a 36 plane alpha strike against that bridge and the North Vietnamese had it running again in 48 hours. The engineers started talking about load paths, etc. I interrupted. “Guys, what we need to know is where to aim, not a justification of the aim point.” They looked disappointed but continued.

“This is the largest span on the bridge. We want as large a span as possible cantilevered to ensure the weight is enough to fail the span and drop it in the river. So where we need to cut it is just shy of this cement piling. Give it about ten or twenty feet so when it drops it misses the piling and goes in the river. They won’t be able to fix that.”

We looked at the pictures and made X’s where we wanted to aim. Then we started looking at the surrounding terrain to get a better idea of what we would see at launch. There was a large hill on the left if we approached it from off shore, which was our plan. The roadway ran around the base of the hill and onto the bridge. The other side was kind of flat and non-distinct. The bridge itself, being large, was probably the most distinct, but the backdrop gave it little contrast.

Off we went again. We got airborne and headed into the target area. Using our code word we selected our weapon stations to bring up the weapon. I selected the Walleye station and then the radar scope. The station indicated the weapon was up but I had nothing on the scope. Usually I put the weapon on something distinct by using the scope, then designated. Then I would move my manual gun sight pipper to the target and undesignate which left the weapon bore sited to my gun sight. But I had no video. Security comm went out the window as I radioed Geno. He commented that was not good.Am I going to have to bring this monster home again? Then Geno came back on the radio.

“Okay, I have video. Fall in behind me.”

Not sure what he was up to, I fell in behind him.

“Drop back behind my number two pylon.” I did as requested.

“Now move up some. Stop! Hold that and designate.” Now I could see his plan. Clever devil.

“Okay, slide back some, move your pipper to the back of my number two pylon and undesignate.”

“Okay, good, you are bore sited. Don’t touch anything until we are ready to launch.”

Now I knew they had the right team for the job. Nice save. I could aim my airplane with the pipper and he could tell me if he saw something he recognized.

We were launching this weapon farther out to keep out of a local SAM site’s range, so we were higher and farther away, probably ten miles. Certainly not something from our book of normal every day operations. Geno set up his race track and I moved in toward the target.

“I am seeing some stuff that looks familiar. Do you have the mountain?”

I replied, somewhat incredulously, “”Yeah, got that.”

“Just put the pipper on the top of the mountain.” Really? Brave sucker.

“Okay, the pipper is on the mountain. Got it?”

“Yeah, that looks great. Release!” I hit the bomb pickle, fell over sideways again and the weapon was away. We were too far out to worry about pictures, which having read about the defenses, did not disappoint me.

Geno tracked down the mountain to the right, found the road and then worked his way out the bridge until he had the span in sight. As the Fat Albert got in closer he tightened up the aim on the specific supporting girder under the bridge. Job done.

Post strike BDA (bomb damage assessment) showed the whole span dropped, just as planned.

Back aboard they brought the wire recorder down from the Intel spaces to the ready room. The cat was pretty much out of the bag in terms of our troops knowing what was going on, plus the skipper wanted to see the video of this thing going into the bridge, all recorded by Geno’s control pod.

We ran the video a couple of times, made positive comments about Geno’s expert guidance and were chatting it up when the skipper said “Run that again.”

We did as commanded.

“Run it again.”

We did it again.

“Run it again and keep your finger on the stop button.”

“Stop!” The skipper had seen what we had not. Just as the weapon was getting so close it was going out of focus, on the left side of the picture, some hapless individual on a bicycle with a straw cooley hat on had his attention focused on some noise coming his way. Poor booger! When I went back through training a few years later, they used this video as part of training, but that last three seconds was cut out.

Well, since we had proven this thing to be a bridge buster, it was time for the big fish. The Thanh Hoa bridge had probably more ordnance thrown against it than any other target in the North, and yet still stood. Girder type bridges do not respond to blast weapons since they have little surface area to unit strength. While we could tear up the roadway, the North Vietnamese would come back in, lay down some new lumber or railroad tracks and get back in business, often overnight. It was maddening.

Our job was to disrupt, which we often did. They had a phenomenal capability of work arounds for river and water crossings, etc. Sometimes when we took out a bridge they would build a floating bridge, and then hide it in the foliage next to the river and bring it out at night. While we were working our tails off trying to stop them it was often only marginally effective. It did give some use to night missions, where the campfires, truck lights, and other indications of activity were often easier to see. But nobody liked combat at night. The combat itself was harrowing, but as proven out by some inventive flight surgeons, our greatest pulse rates, highest blood pressure, most galvanic skin response (sweating} occurred during the night landings, not AAA and SAM encounters. Probably the most disliked was the midnight to noon shift. You got a night cat shot but credit for a day landing. Some argue that the night cat was worse than the landing because in the landing you can rationalize you have some control. Whereas during a night cat shot, after accelerating to 150 knots plus in two seconds, you were shot into the inky blackness 60 feet off the water not knowing whether you were flying or not until the instruments collected themselves a few seconds later. Plus, if you did have a problem and ejected, the ship might run right over you. At least in the daylight one could visually tilt the airplane and hope to have one’s parachute land off to one side of the ship. Wishful thinking, of course, but comforting.

Once again we briefed the specific parts of the bridge. It was obvious this one would take more concentrated effort, since the bridge was stronger and bigger. Plus it was extremely well defended. Its location meant we had to be farther inland and closer to the defenses in order to see and hit the bridge at the angles they needed to be effective. There was some discussion as to whether it would take two Walleyes to do the job. Since there were only three left, they were not keen on committing two at once, or even two at the same target. The prep was basically the same, we figured out where we needed to be relative to the target, which was a bit closer than before. They were also worried that someone would shoot the target down if it had a long glide and were pressing us to move in closer yet. We pointed out that going straight path in Indian country was a good way to get shot down. We settled on a strategy that put us outside of the AAA fire for 23mm and 37mm known to be there. The SAMs were further north and did not seem to be a problem coming in from the east.

The system checked out good, bore site was good, contrast on the radar screen looked good, we were ready to go. Geno set up his orbit and I moved toward the coast. The area is pretty distinct and the bridge is pretty big so I could see the area from a long way out. I established my altitude for dive angle, turned on the scope and weapon and started looking for the bridge. I picked up the shore line on the Ma River and moved the aircraft around a little to bring the aim point up higher. I could see the bridge ends on the scope. As I moved it toward the center of the bridge to find the preferred designation spot, I had a little fuzzy spot on the screen. I moved the aircraft slightly left and right but the fuzzy spot stayed over the bridge. Geno let me know he was ready when I was. I looked outside to see if there was a bug spot on the glass nose of the weapon but it looked fine. When I looked back the fuzzy spot had grown and was covering up more of the bridge.

“Chippy 402, you got the blur on the screen?”

“Affirmative.”

I instinctively raised my head and looked out the window. As I did a bright red flash rocketed past the cockpit and I realized that the blur was a 57mm tracer coming straight at me. I was fortunate it did not activate a proximity fuse going by that close. We had briefed the smaller AAA but had not ever seen low angle 57mm since they usually reserved that caliber for high flyers and higher shot angles. I got the feeling they were pulling out all the stops just to knock us down.

Well, once the fuzz was gone, it was time to get back to work. The bridge was clear and I was rapidly getting closer and in range of defensive fire. I had a good picture and reached for the bomb pickle. The picture snapped up and became blank. At first I thought the radar screen had gone south, but a quick look at the weapon revealed the camera pointing straight up inside of the clear glass nose. Not good.

Walleye Nose

“402, I have a problem, turning outbound to trouble shoot.”

“Roger, not seeing anything on the screen.”

Once outbound and having gained a few miles behind me where I could trust not being shot at, I recycled the weapon switches. Nothing changed. I tried designating to see if the camera would move, nothing. Cycled everything down to the master arm, but it appeared the weapon had failed inside. Good grief, they are going to want this thing back aboard!

Now I had to carefully plan my fuel consumption. I turned off the fuel transfer out of the wings so I could dump that fuel if need be. I needed to be down to around 500 pounds in the main bag at touch down. But I had to be careful because if it went below 400 then motive flow would shut off and I would not be able to transfer fuel from the wings or fuselage if I needed it. That had only recently become evident when we lost an A7 with 4000 pounds of fuel on board to fuel starvation. Geno rendezvoused with me and check the weapon over from the outside but nothing evident was observed except the camera being astray. We both assumed that a gyro in the platform had failed, later to be validated by the engineers.

Now we were approaching the ship awaiting a ready deck. I had plenty of fuel. If things went wrong I could foul the deck. Or a worse scenario, I might have to reef the airplane back around for another quick landing. So the air boss opted to have me land last. Geno kissed me off and descended to land. I took one last look at everything. I was at about 800 pounds in the mains and some left in the wings. Shortly I was given a signal Charlie and on descent hit the dump switch to get rid of the wing fuel. I came into the break at 400 feet and broke downwind. The aircraft felt a little sluggish due to the wing weight, but otherwise felt fine. I rolled out on final and reported “406, ball, point five.” I was exceedingly careful to keep line up and not get overpowered in close. It was a good pass with a centered ball.

I hit the deck, grabbed a three wire and started rolling out. When the cable started decelerating the aircraft swerved very heavily to the right. I though it might have hit a wing tip. So much for the engineer’s momentum calcs. I was lucky there were no airplanes or people on the foul line or I would have collected a few. A bit of a wild ride to be sure! As the airplane settled back on its main mounts, I pulled the hook up, folded the wings, and taxied ahead toward the flight deck director. They tied me down on the elevator in anticipation of taking the aircraft below to download the weapon.

In the post brief I heard what I already knew, that we had been trying to knock that bridge down for about a year. All were pretty disappointed that the weapon did not work, but decided that the opposition we faced might be a bit much for a research and development strike.

The skipper sent me below decks to see the flight surgeon. I was not sure what that was for until I arrived. He offered me an airline bottle of Courvoisier Cognac from his medicinal supplies. All he said was “I heard you earned this.” Another day in paradise! That was the last of my efforts on the project although two more were delivered without much success by other pilots.